Dalio interprets "When Will the Bubble Burst": Stock Market Bubble + Huge Wealth Gap = Enormous Danger

Dalio stated that the US stock market is currently in a bubble, and bubbles do not burst simply because of overvaluation; historically, what truly triggers a crash is a liquidity crisis.

Written by: Zhao Ying

Source: Wallstreetcn

As US stocks plummet, Dalio once again discusses the bursting of bubbles. Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio has issued a fresh warning that the US stock market is currently in a bubble, and extreme wealth concentration is amplifying the market's fragility.

He stated that the bursting of a bubble is not triggered by high valuations, but rather when investors are suddenly forced to sell assets to raise cash for debt repayment or taxes. Against the backdrop of the wealthiest 10% of Americans holding nearly 90% of stocks, the risk of such a liquidity shock is intensifying.

In a media interview on Thursday, Dalio pointed out that although the current situation is not an exact replica of 1929 or 1999, the indicators he tracks show that the US is rapidly approaching a bubble tipping point. "There is indeed a bubble in the market," he said, "but we haven't seen it burst yet. And crucially, there is still a lot of room for upside before the bubble bursts."

It is worth noting that Dalio is not focused on corporate fundamentals, but rather on the fragile structure of the broader market. In the current environment of extreme wealth inequality, record margin debt, and potential policy shocks such as a wealth tax, bubble dynamics are becoming particularly dangerous.

The Trigger for Bubble Bursting Is a Liquidity Crisis

In a lengthy post on X on the same day, Dalio explained that bubbles do not burst simply because of overvaluation. Historically, what truly triggers a crash is a liquidity crisis—when investors are suddenly forced to sell assets on a large scale to raise funds for debt repayment, taxes, or other liquidity needs.

He wrote:

Financial wealth is worthless unless it is converted into money for spending. It is this forced selling, rather than poor earnings reports or shifts in sentiment, that has historically driven market crashes.

The factors contributing to current market fragility are accumulating. Margin debt has reached a record $1.2 trillion. California is considering a one-time 5% wealth tax on billionaires, which is precisely the kind of policy shock that could trigger large-scale asset liquidation. "Tightening monetary policy is the classic trigger," Dalio said, "but things like a wealth tax could also happen."

K-Shaped Economy Amplifies Market Fragility

Dalio particularly emphasized that the current concentration of wealth is greatly amplifying this fragility. The wealthiest 10% of Americans now hold nearly 90% of stocks and account for about half of consumer spending. This concentration masks the deterioration among the lower half of the income ladder, creating what economists widely describe as a "K-shaped economy"—with high-income households soaring while everyone else falls further behind.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Analytics, recently found that the wealthiest households are driving almost all consumption growth, while low-income Americans are cutting back under the pressure of tariffs, high borrowing costs, and rent inflation.

Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, described this inequality as "completely crazy," noting that spending growth among wealthy households is six to seven times that of the lowest-income group. Even Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has acknowledged this divide, saying that companies report "the economy is showing a split," with high-income consumers continuing to spend while others are downgrading their consumption.

How to Respond to Bubble Risks?

Despite his warning, Dalio did not advise investors to abandon the current rally. He stated that bubbles can last far longer than skeptics expect and can deliver huge gains before they burst. His advice is that investors need to understand the risks, diversify, and hedge—he specifically mentioned gold, which has hit record highs this year.

"I want to reiterate, there is still a lot of room for upside before the bubble bursts," he said. But he warned in the article: "Historically, these situations have led to great conflict and massive transfers of wealth."

Dalio's warning and Nvidia's triumph both acknowledge that the market is accelerating in ways that traditional models struggle to explain. The AI boom may continue to drive the stock market higher, but the bubble mechanisms Dalio outlines—easy credit, wealth concentration, and vulnerability to liquidity shocks—are also tightening in tandem.

Below is the full text of Dalio's post:

While I remain an active investor and passionate about investing, at this stage of my life, I am also a teacher, striving to pass on what I have learned about how reality works and the principles that have helped me deal with it. Having been engaged in global macro investing for over 50 years and having learned many lessons from history, naturally, much of what I pass on is related to this.

This article aims to explore:

- The important distinction between wealth and money,

- How this distinction drives bubbles and depressions, and

- How this dynamic, combined with a huge wealth gap, can potentially burst bubbles and lead to depressions that are destructive both financially and socially and politically.

Understanding the difference and relationship between wealth and money is crucial, most importantly: 1) how bubbles form when the scale of financial wealth becomes very large relative to the amount of money; 2) how bubbles burst when people need money and are forced to sell wealth to get it.

This very basic and easy-to-understand concept about how things work is not widely recognized, but it has greatly helped my investing.

The main principles to understand are:

- Financial wealth can be created very easily, but does not represent real value;

- Financial wealth is worthless unless it is converted into spendable money;

- Converting financial wealth into spendable money requires selling it (or collecting its income), which usually leads to the bursting of bubbles.

Regarding "financial wealth can be created very easily and does not represent real value," for example, today if a startup founder sells company shares—say, worth $50 million—and values the company at $1 billion, then the seller becomes a billionaire. This is because the company is considered worth $1 billion, even though there is nowhere near $1 billion in real money backing up that wealth figure. Similarly, if a buyer of publicly traded stock purchases a small number of shares from a seller at a certain price, all shares are valued at that price, so by valuing all shares at that price, you can determine the total amount of wealth in the company. Of course, the actual value of these companies may not be as high as these valuations, because the value of assets is only what they can be sold for.

Regarding "financial wealth is basically worthless unless converted into money," this is because wealth cannot be directly consumed, but money can.

When the amount of wealth is large relative to the amount of money, and wealth holders need to sell wealth to get money, the third principle applies: "Converting financial wealth into spendable money requires selling it (or collecting its income), which usually turns bubbles into depressions."

If you understand these, you can understand how bubbles form and how they burst into depressions, which will help you predict and deal with bubbles and depressions.

It is also important to understand that while both money and credit can be used to buy things, a) money settles transactions, while credit creates debt that requires money in the future to settle; b) credit is easy to create, while money can only be created by central banks. While people may think that money is needed to buy things, this is not entirely true, because people can buy things with credit, which creates debt that needs to be repaid. This is usually the ingredient of bubbles.

Now, let’s look at an example.

Although throughout history, all bubbles and bubble bursts essentially operate the same way, I will use the bubble of 1927-1929 and the bursting of the bubble from 1929-1933 as an example. If you think about the late 1920s bubble, the 1929-1933 bubble burst and depression, and the measures President Roosevelt took in March 1933 to ease the bursting of the bubble from a mechanistic perspective, you will understand how the principles I just described work.

What funds drove the stock market boom that ultimately formed the bubble? And where did the bubble come from? Common sense tells us that if the money supply is limited and everything must be bought with money, then buying anything means diverting funds from something else. Due to selling, the price of the diverted item may fall, while the price of the purchased item may rise. However, at that time (for example, in the late 1920s) and now, what drove the stock market boom was not money, but credit. Credit can be created without money and used to buy stocks and other assets that make up the bubble. The mechanism at the time (and the most classic mechanism) was: people created and borrowed credit to buy stocks, thus creating debt, and this debt had to be repaid. When the funds needed to repay the debt exceeded the funds generated by the stocks, financial assets had to be sold, causing prices to fall. The process of bubble formation in turn led to the bursting of the bubble.

The general principles of these dynamic factors driving bubbles and bubble bursts are:

When financial asset purchases are mainly driven by credit growth, causing wealth to grow relative to the amount of money (i.e., wealth far exceeds money), a bubble forms; and when wealth needs to be sold to raise funds, the bubble bursts. For example, during 1929 to 1933, stocks and other assets had to be sold to repay the debt used to buy them, so the mechanism of the bubble reversed. Naturally, the more borrowing and stock buying, the better stocks performed, and the more people wanted to buy. These buyers could buy stocks without selling anything else because they could buy with credit. As credit purchases increased, credit tightened, and interest rates rose, both because borrowing demand was strong and because the Federal Reserve allowed rates to rise (i.e., tightened monetary policy). When borrowing had to be repaid, stocks had to be sold to raise funds to repay the debt, so prices fell, defaults occurred, collateral values fell, credit supply shrank, and the bubble turned into a self-reinforcing depression, followed by the Great Depression.

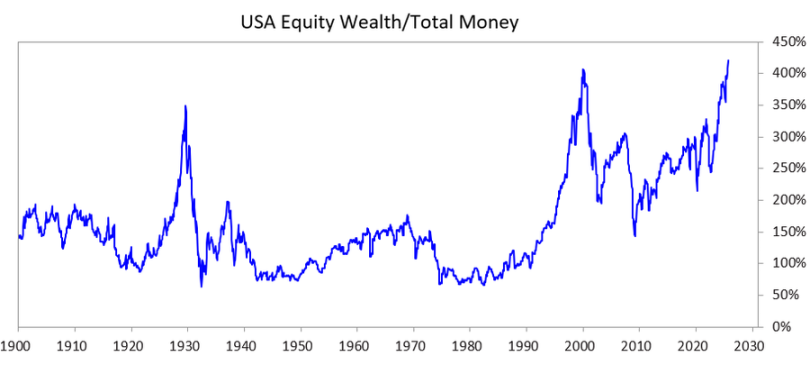

To explore how this dynamic, combined with a huge wealth gap, can burst bubbles and lead to a crash that could be devastating socially, politically, and financially, I analyzed the chart below. It shows the past and present wealth/money gap, as well as the ratio of total stock value to total money value.

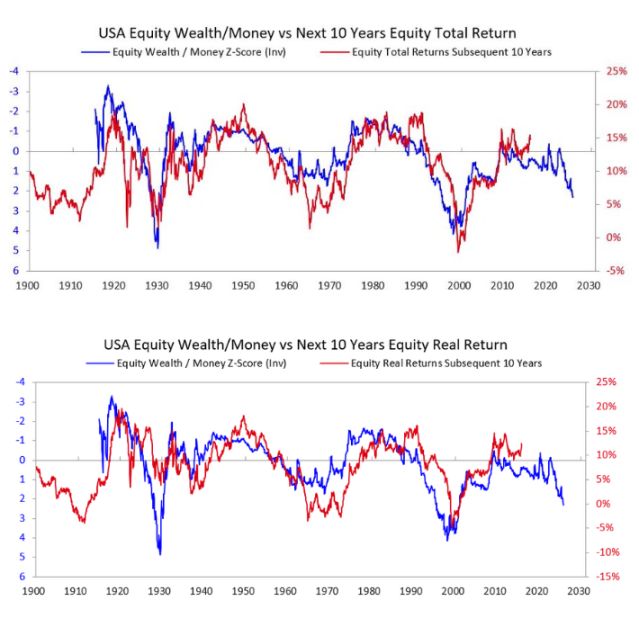

The next two charts show how this reading predicts nominal and real returns over the next 10 years. The charts speak for themselves.

When I hear people try to judge whether a stock or the stock market is in a bubble by assessing whether a company will eventually become profitable enough over time to provide sufficient returns at current prices, I think they do not understand bubble dynamics. While how much an investment will ultimately earn is of course important, it is not the main reason bubbles burst. Bubbles do not burst because people wake up one morning and decide there will not be enough income and profits in the future to justify the price. After all, whether there will be enough income and profits to support a good investment return usually takes many years, even decades, to become clear. The principle to keep in mind is:

Bubbles burst because the flow of funds into assets begins to dry up, and holders of stocks and/or other wealth assets need to sell them for some reason (most commonly to pay off debts) to get money.

What usually happens next?

After the bubble bursts, when there is not enough money and credit to meet the needs of financial asset holders, the market and economy go into recession, and internal social and political turmoil usually intensifies. If there is a huge wealth gap, this is especially true, as the wealth gap exacerbates the divide and anger between the rich/right and the poor/left. In the 1927-33 case we are examining, this dynamic led to the Great Depression, which triggered huge internal conflict, especially between the rich/right and the poor/left. This dynamic led to President Hoover being ousted and Roosevelt being elected president.

Naturally, when the bubble bursts and the market and economy go into recession, these situations lead to major political changes, huge deficits, and massive debt monetization. In the 1927-33 example, the market and economic downturn occurred from 1929-32, political change occurred in 1932, and these situations led to President Roosevelt's administration running huge budget deficits in 1933.

His central bank printed large amounts of money, causing currency devaluation (e.g., relative to gold). This currency devaluation eased the money shortage and: a) helped those systemically important debtors who were squeezed to repay their debts; b) pushed up asset prices; c) stimulated the economy. Leaders who come to power during such periods also tend to make many shocking fiscal reforms, which I cannot explain in detail here, but I can say for sure that these periods often lead to huge conflict and massive transfers of wealth. In Roosevelt's case, these situations led to a series of major fiscal policy reforms aimed at transferring wealth from the top to the bottom (e.g., raising the top marginal income tax rate from 25% in the 1920s to 79%, sharply increasing estate and gift taxes, and greatly expanding social welfare programs and subsidies). This also led to huge conflict both within and between countries.

This is the typical dynamic. Throughout history, countless leaders and central banks in too many countries, over too many years, have repeated the same mistakes countless times, which I cannot enumerate here. By the way, before 1913, the US had no central bank and the government had no power to print money, so bank defaults and deflationary depressions were more common. In either case, bondholders suffered losses, while gold holders did very well.

While the 1927-33 example nicely illustrates the classic bubble-depression cycle, it is one of the more extreme cases. You can see the same dynamics in the events that led President Nixon and the Federal Reserve to do exactly the same thing in 1971, as well as in almost all other bubbles and depressions (e.g., Japan in 1989-90, the dot-com bubble in 2000, etc.). These bubbles and depressions have many other typical characteristics (e.g., markets are very popular with inexperienced investors, who are drawn in by the heat, buy with leverage, lose heavily, and then become angry).

This dynamic pattern has existed for thousands of years (i.e., money demand exceeds supply). People are forced to sell wealth to get money, bubbles burst, followed by defaults, money printing, and poor economic, social, and political outcomes. In other words, the imbalance between financial wealth and the amount of money, and the act of converting financial wealth (especially debt assets) into money, has always been the root cause of bank runs, whether in private banks or government-controlled central banks. These runs either lead to defaults (which mostly happened before the Fed was established) or prompt central banks to create money and credit to provide to those systemically important institutions that cannot be allowed to fail, ensuring they can repay loans and avoid bankruptcy.

So, remember:

When the promises to pay money (i.e., debt assets) far exceed the amount of money in existence, and there is a need to sell financial assets to get money, beware of bubbles bursting and make sure you are protected (e.g., do not have significant credit risk exposure and hold some gold). If this happens at a time of a huge wealth gap, beware of major political and wealth changes and be sure to protect yourself.

While rising interest rates and tightening credit have always been the most common reasons for selling assets to get the money needed, any reason that creates demand for money—such as a wealth tax—and the sale of financial wealth to obtain that money, can trigger this dynamic.

When there is both a huge wealth/money gap and a huge wealth gap, this should be considered a very dangerous situation.

From the 1920s to the Present

(If you do not want to read a brief description of how we got from the 1920s to today, you can skip this section.)

While I mentioned how the bubble of the 1920s led to the depression and Great Depression of 1929-33, to quickly bring you up to date, that depression and the ensuing Great Depression led President Roosevelt in 1933 to default on the US government's promise to deliver then-hard currency (gold) at the promised price. The government printed large amounts of money, and the price of gold rose by about 70%. I will skip over how the reflation of 1933-38 led to the tightening of 1938; how the "recession" of 1938-39 created the conditions for economic and leadership change, combined with the geopolitical dynamics of Germany and Japan rising to challenge the Anglo-American powers, leading to World War II; and how the classic long-cycle dynamics took us from 1939 to 1945 (when the old monetary, political, and geopolitical order collapsed and a new order was established).

I will not go into the reasons in depth, but it should be noted that these factors made the US very wealthy (at the time, the US held two-thirds of the world's money, all of which was gold) and powerful (the US created half of the world's GDP and was the military hegemon at the time). Therefore, when the Bretton Woods system established a new monetary order, it was still based on gold, with the dollar pegged to gold (other countries could use the dollars they earned to buy gold at $35 an ounce), and other countries' currencies were also pegged to gold. Then, from 1944 to 1971, US government spending far exceeded tax revenue, so it borrowed heavily and sold these debts, creating gold claims far in excess of central bank gold reserves. Seeing this, other countries began to exchange their paper money for gold. This led to an extreme tightening of money and credit, so President Nixon in 1971 did what Roosevelt did in 1933, once again devaluing fiat currency relative to gold, causing gold prices to soar. Needless to say, from then until now, a) government debt and the cost of servicing it have risen sharply relative to the tax revenue needed to repay it (especially during 2008-2012 after the global financial crisis and after the financial crisis triggered by COVID-19 in 2020); b) income and value gaps have widened to today's levels, creating irreconcilable political divisions; c) the stock market may be in a bubble, and the bubble is being driven by speculation on new technologies supported by credit, debt, and innovation.

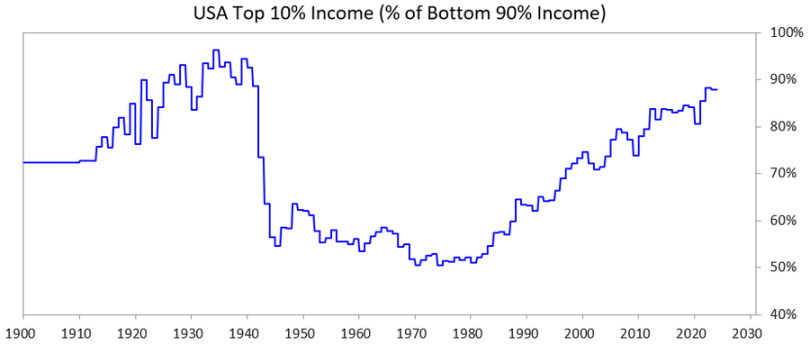

The chart below shows the income share of the top 10% relative to the bottom 90%—you can see how large the gap is today.

Where We Are Now

The US, as well as all other heavily indebted democratic governments, now face the dilemma that: a) they cannot increase debt as before; b) they cannot significantly raise taxes; c) they cannot significantly cut spending to avoid deficits and debt increases—they are stuck.

To explain in more detail:

They cannot borrow enough money because there is not enough free market demand for their debt. (This is because they are already over-indebted, and debt holders already hold too much of their debt.) In addition, international holders of other countries' debt assets worry that conflict akin to war may prevent them from getting their money back, so their willingness to buy bonds is reduced, and they shift their debt assets into gold.

They cannot raise taxes enough because if they tax the top 1-10% (who own most of the wealth), a) these people will leave, taking their tax payments with them, or b) politicians will lose the support of the top 1-10% (which is important for funding expensive campaigns), or c) they will burst the bubble.

They cannot cut spending and welfare enough because this is politically, and perhaps morally, unacceptable, especially since such cuts would disproportionately affect the bottom 60%...

...so they are stuck.

For this reason, all indebted, wealthy, and value-divided democratic governments are facing a dilemma.

Given these conditions, the way democratic political systems work, and human nature, politicians promise quick fixes, fail to deliver satisfactory results, and are quickly ousted and replaced by new politicians who promise quick fixes, fail, and are replaced, and so on. That is why the UK and France (both of which have systems that allow for rapid leadership changes) have each changed prime ministers four times in the past five years.

In other words, what we are seeing now is the classic pattern typical of this stage of the long cycle. Understanding this dynamic is very important, and it should now be obvious.

Meanwhile, the stock market and wealth boom are highly concentrated in top AI-related stocks (e.g., the Magnificent Seven) and a handful of super-rich individuals, while AI is replacing labor, exacerbating the wealth/money gap and the gap between people. This dynamic has occurred many times in history, and I believe it is highly likely to trigger a strong political and social backlash, at the very least significantly changing the pattern of wealth distribution, and in the worst case, leading to serious social and political turmoil.

Now let’s look at how this dynamic and the huge wealth gap together create problems for monetary policy and could lead to a wealth tax, bursting the bubble and causing a depression.

The Data Situation

I will now compare the top 10% of wealth and income holders with the bottom 60%. I choose the bottom 60% because they make up the majority of the population.

In short:

- The wealthiest (top 1-10%) have far more wealth, income, and stock ownership than the majority (bottom 60%).

- Most of the wealth of the richest comes from appreciation, which is not taxed until sold (unlike income, which is taxed when earned).

- With the AI boom, these gaps are widening and may accelerate further.

- If a wealth tax is imposed, assets will need to be sold to pay the tax, which could burst the bubble.

More specifically:

In the US, the top 10% of households are well-educated and highly economically productive, earning about 50% of total income, owning about two-thirds of total wealth, holding about 90% of all stocks, and paying about two-thirds of federal income taxes—all of which are steadily increasing. In other words, they are doing well and contributing a lot.

In contrast, the bottom 60% are less educated (for example, 60% of Americans read below a sixth-grade level), less economically productive, collectively earn only about 30% of total income, own only 5% of total wealth, hold only about 5% of all stocks, and pay less than 5% of federal taxes. Their wealth and economic prospects are relatively stagnant, so they feel financially squeezed.

Of course, there is enormous pressure to tax wealth and money and redistribute it from the wealthiest 10% to the poorest 60%.

Although we have never imposed a wealth tax, there is now great pressure at both the state and federal levels to introduce such a tax. Why was it not taxed before, but now there is pressure for a wealth tax? Because the money is concentrated in wealth—that is, most of the top people's wealth growth comes not from earned income, but from untaxed appreciation.

There are three major problems with a wealth tax:

- The wealthy can choose to move, and if they do, they take their talent, productivity, income, wealth, and tax payments with them, reducing these elements in the place they leave and increasing them in the place they go;

- A wealth tax is difficult to implement (for reasons you may know, and I do not want to digress as this article is already too long);

- A wealth tax diverts funds from investments that finance productivity improvements to the government, based on the unlikely assumption that the government can handle these funds well enough to make the bottom 60% productive and prosperous.

For these reasons, I would rather see a tolerable tax on unrealized capital gains (e.g., a 5-10% tax). But that is another topic for another time.

P.S.: So how would a wealth tax work?

I will discuss this issue more fully in future articles. Suffice it to say, the US household balance sheet shows about $150 trillion in total wealth, but less than $5 trillion of that is in cash or deposits. Therefore, if a 1-2% annual wealth tax were imposed, the annual cash demand would exceed $1-2 trillion—and the pool of liquid cash is not much bigger than that.

Any such measure would puncture the bubble and cause an economic collapse. Of course, a wealth tax would not be imposed on everyone, but only on the wealthy. This article is already long enough, so I will not elaborate on the specific numbers. In short, a wealth tax would: 1) trigger forced selling of private and public equity, depressing valuations; 2) increase credit demand, potentially raising borrowing costs for the wealthy and the entire market; 3) encourage offshore transfers of wealth or moves to more government-friendly jurisdictions. If the government imposes a wealth tax on unrealized gains or illiquid assets (such as private equity, venture capital, or even concentrated holdings of public equity), these pressures will become particularly severe.